COVID winter plan: UK blueprint doesn’t go far enough – here’s a health expert’s alternative

With winter on the horizon, Oxford's Professor of Primary Care Health Sciences, Trish Greenhalgh, suggests alternative UK blueprint, focusing on precautions that allow the British public to learn to live (as opposed to dying of) COVID.

©

Shutterstock

©

Shutterstock

UK prime minister Boris Johnson recently announced a fuzzy blueprint for his “winter plan”, in which further lockdowns and compulsory mask-wearing were not being introduced but could not be ruled out. As an interdisciplinary researcher specialising in complex systems and health policy, it looks to me like the UK is on course for yet another yo-yo winter in which too few precautions are introduced too late, only after the exponential increase in cases and deaths become too dramatic to brush aside.

Unless the British public learns to live with (as opposed to keep dying of) COVID, this cycle could continue indefinitely.

Here’s an alternative blueprint:

1. We agree to take the virus seriously

We must acknowledge that this virus is wily, pernicious and deadly. While some people – including most of those who are fully vaccinated – experience only mild symptoms, significant numbers are hospitalised. COVID has a fatality rate ten times that of seasonal flu. With case numbers remaining high, this means over 1,000 COVID deaths a week in the UK.

This is not OK. Nor is the long tail of chronic and long-term illness being left in the virus’s wake. Neither the so-called clinically vulnerable nor previously healthy young people are expendable in the name of “normality”. Indeed, we should be clear that normality is a situation where long-term debilitation or death from infectious disease is vanishingly rare.

2. We commit to ‘air hygiene’ as we commit to food hygiene and clean water

We will never control this virus if we continue to delude ourselves about how it spreads. The early and bold announcement by the World Health Organization that the virus is spread by droplets (coughs, sneezes, skin-to-skin transmission and contaminated objects and surfaces) led to ineffective global prevention policies that focused on handwashing, surface cleansing, avoiding close physical contact and quarantining of objects.

The scientific evidence that this virus spreads predominantly through the air – especially via super-spreader events in which dozens or hundreds of people inhale viral-laden aerosols exhaled by an infected individual – was ignored for months. Preventing the spread of airborne infection requires better ventilation of indoor spaces, more effective and closer-fitting masks, reducing crowding indoors, continuing two-metre physical distancing and reducing the amount of time people spend indoors.

Longer-term, we need to redesign buildings to maximise ventilation.

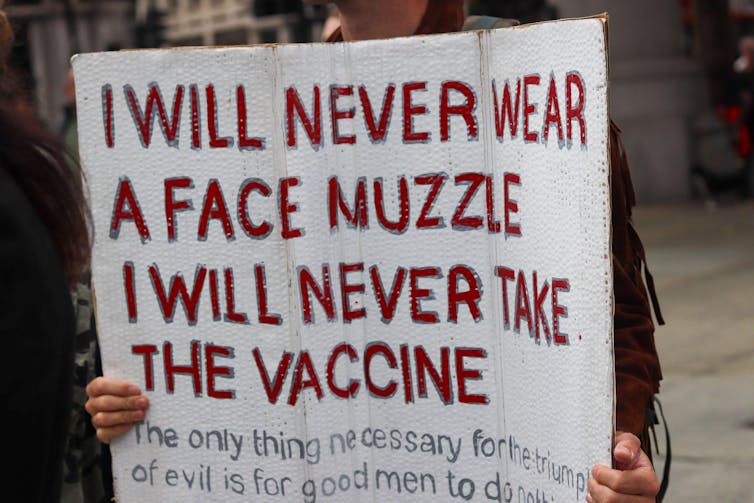

3. We use masks to make society freer and safer

Masks were quickly seized by libertarians as a symbol of oppression. Actually, masks are the simple measure that could allow us to keep society open and maintain near-normal activities – such as travelling on public transport, going to work, shopping, attending school – safely even while the virus continues to circulate. Masks aren’t perfect, but well-fitting masks, worn consistently, filter out the vast majority of airborne particles and dramatically reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

Masks were seen as a symbol of oppression. MI News & Sport/Alamy Stock Photo

Masks were seen as a symbol of oppression. MI News & Sport/Alamy Stock Photo

4. We aim to vaccinate almost everyone

The rapid development of several effective and safe COVID vaccines is one of the greatest scientific achievements of the 21st century. A fully vaccinated person can expect an 80% reduction in the risk of developing COVID and an even greater reduction in the risk of death. While there is some evidence that the delta variant can still be passed on by fully vaccinated people, vaccination still reduces both the likelihood of transmission and the viral load – which relates to the severity of the disease.

Reasons for low vaccine uptake (for example, in older people from certain minority ethnic groups) should be identified and addressed. Teenagers, too, should be vaccinated. The risks of vaccine-related myocarditis in teenage boys have been vastly inflated. In reality, this complication is extremely rare, never fatal – although it can take several weeks for the person to recover fully – and both less common and less serious than the myocarditis that happens with COVID infection.

5. We value and support public deliberation

COVID has profoundly affected our lives, lifestyles and sense of freedom. The trade-offs between continuing restrictions and “acceptable” levels of illness and death are complex, not least because the burden of restrictions is borne disproportionately by some groups, such as small-business owners, those commuting by public transport, and those working in low-paid and low-skill jobs. Lifting restrictions also causes disproportionate risks, for example, for the clinically extremely vulnerable (such as those undergoing chemotherapy).

The many unknowns include the risks and long-term prognosis of long COVID, when and how the virus will mutate again to escape current vaccines, and the nature and extent of animal reservoirs (animals that are the source of zoonotic diseases). Minimising concerns or denying the existence of risks will not solve the challenges we face.

Public consultation is one of the hallmarks of an advanced democracy, and ongoing open and honest deliberation, even among those with opposing views, is needed to decide on fair and reasonable long-term measures that will protect public health, enable society to function and minimise inequality and disadvantage.

Thanks to Mr Adam Hamdy, independent researcher in pandemic response, for advice on this article.

This article was published in The Conversation.

Disclosure statement: Trish Greenhalgh receives funding from National Institute for Health Research (BRC-1215-20008), ESRC (ES/V010069/1), Wellcome Trust (WT104830MA) and Health Data Research UK (HDRUK2020.139).

What to read next

COVID: Seven reasons mask wearing in the west was unnecessarily delayed

15 July 2021

Masks help prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, yet masking policies in the west have featured some spectacular policy wrong turns, says Professor Trish Greenhalgh.

COVID: the reason cases are rising among the double vaccinated – it’s not because vaccines aren’t working

22 July 2021

Sir Patrick Vallance, the UK’s chief scientific adviser, has announced that 40% of people admitted to hospital with COVID in the UK have had two doses of a coronavirus vaccine. At first glance, this rings very serious alarm bells, but it shouldn’t. The vaccines are still working very well.

COVID: media must rise above pitting scientists against each other – dealing with the pandemic requires nuance

26 July 2021

Professors Trisha Greenhalgh and Dominic Wilkinson call upon the media to rise above presenting the false adversarial narrative of 'pro' and 'anti' this and that, and instead embrace scientific and moral uncertainty for what it is.